Author: Mary Seelhorst

When you do everything right, nothing happens: Remembering Donald C. Seelhorst

I didn’t intend for the theme of my history blog to evolve into “remembering dead relatives.” But without stories about dead people, there would be no history. And the planets keep aligning in ways too relevant to ignore. I’m not even including tonight’s uber-rare conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn, which I won’t be able to see because it’s winter in Michigan. The clouds haven’t lifted all week.

Today’s alignment: this year’s winter solstice marks the 20th anniversary of my dad’s death—December 21, 2000—and it comes as the world’s most massive public health effort gets underway in earnest: administering the Covid-19 vaccine globally. This after the previous massive public health effort—persuading everyone on the planet to wear a mask—failed. At least here in the US.

My dad made a career in public health. Looking back, it’s easy to see why.

His father, Arthur F. Seelhorst Sr, had lived in Philadelphia during the Spanish Flu pandemic. He survived that, married in 1920, had two boys, then caught tuberculosis and died in 1924 at age 28. It was a long, slow death. There’s a reason it was called consumption. My dad was six months old, too young to remember his father.

Then my dad contracted TB as a teenager in the late 1930s. He had what they called the “rest cure”—and only added “cure” if it worked. He isolated and rested, hoping his body could keep the bacteria at bay. It took more than a year to recover. His lungs were never quite the same.

Yes, he isolated while he was contagious. Before penicillin became widely available after World War II—and even for some time afterward, dedicated TB hospitals were common, keeping patients away from others they might infect. Tuberculosis was far less transmissible than this new coronavirus—but today many people won’t even wear a mask, let alone agree to isolate as radically as TB patients once did. Luckily for him, he was able to isolate at home and didn’t have to go away.

Dad used to say, “In public health if you do everything right, nothing happens. But then when nothing happens, people think you went too far.” That’s what you want—nothing. No one dies, businesses don’t close, life isn’t disrupted. Imagine if nothing had happened in 2020.

Another of his favorites was “Public health is always underfunded and underappreciated.” That’s only gotten worse since he died twenty years ago.

After graduating from McKell High School in South Shore, Kentucky—delayed a few years because of his illness—he attended a vocational school, intending to stay in Kentucky and farm. He got married in 1951. He and my mom wanted to start a dairy farm, but such an investment was beyond their ability. So instead, Mom worked as a secretary in Portsmouth, Ohio, living with his mother on the Kentucky side of the river to save money while Dad went to school at Marshall University in Huntington, West Virginia. He lived on peanut butter sandwiches during the week and came home on weekends. (Mom said she went to see him at school once and found his closet full of empty peanut butter jars.) Yes, there were lots of Ohio River crossings–including when us kids were born. Everybody in that part of Kentucky went to the Portsmouth hospital.

Dad worked at first for the Vinton County Health Department, a rural county in Southeastern Ohio, then for Athens County next door. He inspected kitchens in public facilities and restaurants, tested well water, and investigated outbreaks of—well, I don’t know—whatever was breaking out. I remember getting a typhoid shot one year when the flooding was bad. Once be brought home a bat in a big jar. It had bitten a kid at a school he was inspecting, so he took it to the lab the next day to be tested for rabies. I wondered what would happen if the jar broke.

Then for about 30 years, he worked for the state, inspecting nursing homes for the Southeast District Ohio Department of Health. Yeah, nursing homes, where this new virus is gripping our elders and their caretakers with fear and far too often death. He’d be horrified at what’s happening in nursing homes today, residents cut off from their families and too often dying despite the best efforts of often underpaid staff at risk of illness from working without enough protective gear.

Every year, all the public health workers had to get a TB test. Every year, he told them it would come back positive. Every year, it did. The bacteria never really leaves–it goes dormant in calcified nodes in the lungs. TB literally dogged his life. (Now that I think about it, if not for tuberculosis, his father wouldn’t have died when he did, his mom wouldn’t have moved to Kentucky when she did, Dad wouldn’t have met Mom, and I wouldn’t be here.)

Two events in his state health department career stand out in my mind. First, a nighttime fire at a Marietta nursing home that killed a large number of residents. They didn’t burn to death—they died from smoke inhalation because the staff had propped open a couple of fire doors that were supposed to automatically close. And they didn’t notice the flashing silent alarm right away because they were watching TV. Dad came home reeking of smoke and spread out the facilities’ floor plans on the floor. I remember he had carpet samples he lit on fire in the back yard to see how much it smoked.

He said it was one of the best homes in the district. “Regulations don’t help if people violate them.”

The other standout moment was not part of his official duties, but informed by his education and experience. About 1980, Grandma Burke was in the hospital (yup, another Kentuckian treated in Portsmouth) with a respiratory illness that mystified her doctor. Dad went to see Grandma, talked to her a bit, then went to find her doctor. “Did you test her for TB?” he asked her doctor.

“No, we never see that any more,” he said.

“Did you ask her where she was this winter?”

“No.”

“Well, she was in Florida for a couple months. Every week, she used a laundromat frequented by Haitian immigrants. There’s been a sharp rise in tuberculosis in Haiti. And I had TB myself. I know the symptoms.”

He was right. She had TB. That night, Dad called me. “You went to see Grandma, right?”

“Of course!” I said defensively, thinking he was checking up on whether I had turned out to be a decent human being.

“Go get a TB test. Now!”

Contact tracing at its finest.

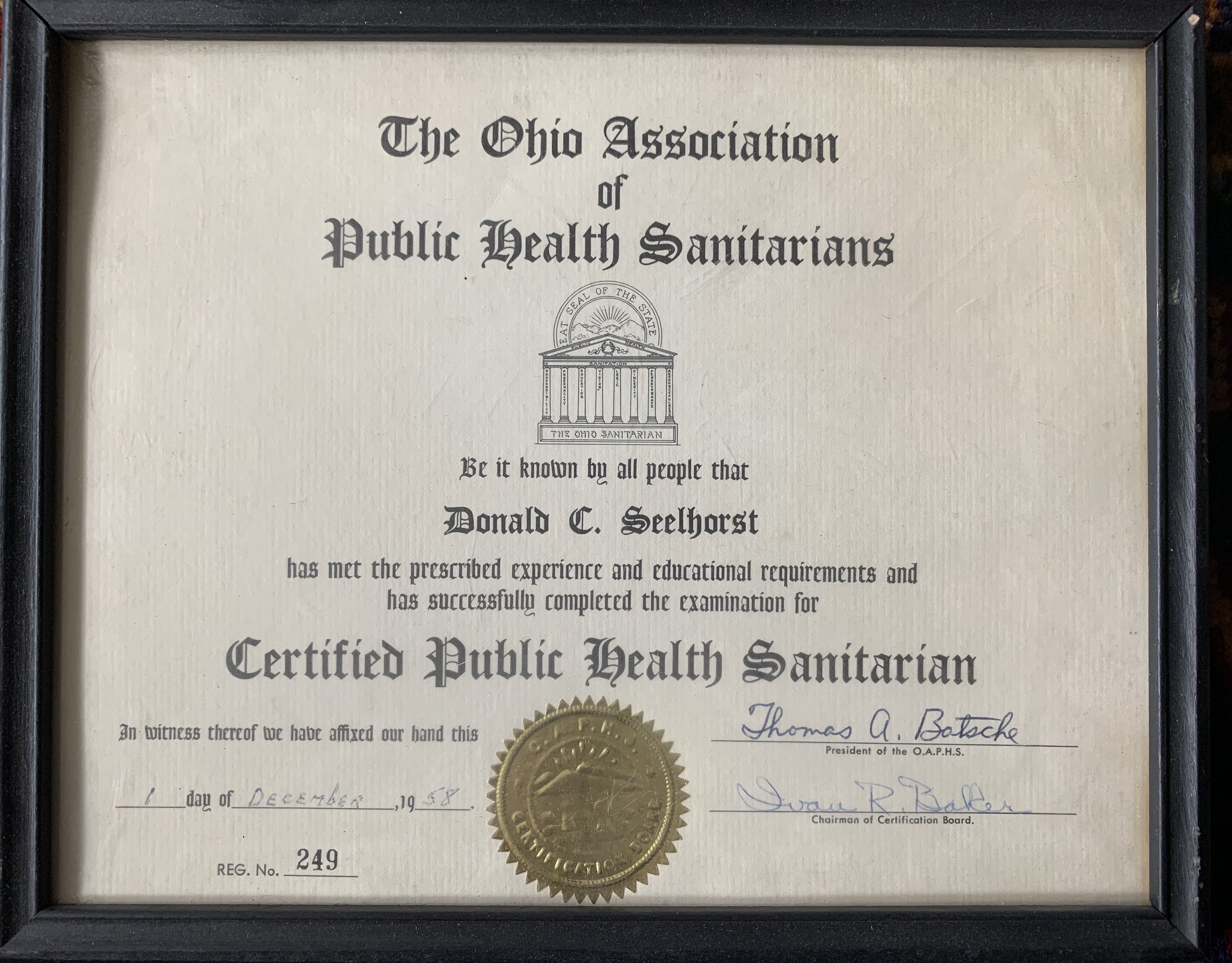

When I was in school, kids would sometimes ask what my dad did. “My dad’s a sanitarian.” They thought it was a euphemism for a garbage collector. In fact, picking up the trash is part of the overarching public health system. It’s not run by the Health Department but, like sewage treatment and municipal water systems, it’s critical to the health of our communities.

I used to wonder why garbage men didn’t make the most money of all. Why didn’t we pay people doing the exhausting and unglamorous and smelly jobs the most? If I could grow up lucky enough to be an artist or a musician, or a writer—well the joy of it would be worth a lot. The privilege of not having to pick up the trash would be worth a lot to me.

Little did I know then that A) most artists and writers and musicians don’t make much money either, and B) the world didn’t work that way.

Maybe it should. The essential workers of this pandemic are the folks with those exhausting and unglamorous jobs: the meat cutters, lettuce pickers, hospital aides, grocery cashiers, bus drivers, mail deliverers, and “sanitation engineers” of all types.

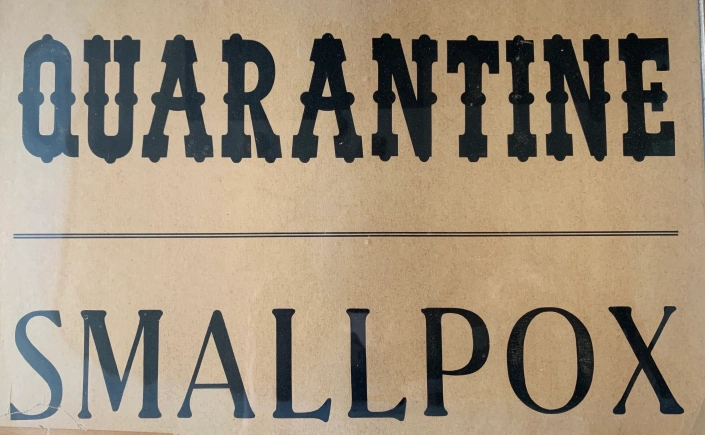

Dad collected several old quarantine signs and other health memorabilia over his career. When Mom could no longer climb the stairs to see them and object, he hung them on the bedroom doors at our house. Sanitation humor. (Yeah, one of them was for tuberculosis. I didn’t end up with that one.)

His old quarantine signs are reminders of the collective actions that communities were once willing to take until science and medicine could catch up and suppress disease. We became so accustomed to relying on science and medicine that we forgot the communal acts of public health that, not so long ago, were all we could rely on to protect each other and ourselves. We forgot what – and who – are essential.

I haven’t forgotten my dad. Even 20 years after his death I remember his smile, his voice, his laugh, and the lessons he taught us. They’re the simple ones. Wash your hands. Cover your cough. Take your medicine.

“If you don’t want to do it for yourself, do it for others.”

The Telltale Part: Reckoning with Artifactual Correctness

This stock photo hit my inbox recently in an email exhorting me to do something—I don’t remember what—with my WordPress website. I don’t remember because when I saw this photo I laughed out loud and read no further. Really laughed, not just a toss-off LOL.

At a glance I could tell the photographer and hand model had never used a manual typewriter before. How did I know? Let me count the ways.

- There’s no paper in the carriage (aka the long cylinder on top that’s supposed to hold the paper).

- There’s no ribbon (an ink-infused ribbon, carried on spools, that the metal type strikes to impress ink onto the paper).

- The “wrists down” position might work for typing on a computer keyboard, but is almost impossible on a manual typewriter, which requires keys to be pressed with some force, straight down, without accidentally striking others.

- The carriage is extra wide, intended for large documents such as maps, blueprints, etc., not for home use as shown in this photo.

- The cover is missing, which doesn’t prevent typing but does keep dirt out of the machine.

It’s possible the photographer did know the typewriter setup wasn’t right but assumed—probably correctly—that most viewers wouldn’t know or care.

But some do.

The errors were obvious to me because I’m old enough that I learned to type on a manual. But looking at this photo made me wonder, what if I didn’t know? What if I’d seen this vignette in a museum? With apologies to Edgar Allan Poe, is a wrong or missing “telltale part” meaningful or trivial?

Given the work I do, you’re probably not surprised that I think it’s important for museums and historic sites to do the hard work of researching not just what a thing is and what it was used for, but how and why it was used.

What were the steps taken before, during, and after using it? What other items or supplies might that activity require? How was it made? How would it have been repaired and maintained? Are parts are missing? Are those extra parts spares or were they also used in some way? Would the user have likely been trained in its use or picked it up by observation and experience? Was it modified by the user? If so how and why?

Museums—along with schools—are one of the few places people visit with an expectation of learning something, and we need to take that seriously. Studies show that people consider museums highly authoritative sources of information. How many times have you gone to a museum on a subject you know well and spotted something—like this typewriter—that’s not right? Did you trust rest of the museum’s offerings more or less after that? Did it stick in your memory? Did you recommend the museum to others after that?

I once went to a small museum with an exhibit on native plants eaten by indigenous peoples. The label about Jerusalem artichokes was illustrated with—you guessed it—a green globe artichoke, not the brown tuber that should have been there. While I’m sure both are delicious with drawn butter and garlic, only one was cultivated by Native Americans as a food source. Michigan artichoke farms are legendary, don’t you know? Almost as popular as our orange and banana orchards.

Seeing the wrong artichoke made me mistrust everything else in the museum. I left and never returned.

Decades ago, I took my mother to an outdoor living history museum where I worked. I showed her around and stopped at a field where a coworker was plowing with a horse.

My mother was raised on a family farm in Eastern Kentucky and knew about plowing with mules the same way I know about using typewriters: she grew up with it. She stood there quietly for a few minutes.

I didn’t say anything, knowing she didn’t need an explanation.

Finally, she said quietly, “He hasn’t done this very much, has he?”

It was more a statement than a question. And she was right. It was a powerful reminder that our visitors often know more than we think.

It’s even more important to get it right when our visitors aren’t experts because they trust us. We need to be worthy of that trust, especially now as we face a global pandemic and a continuing assault on truth, science, and journalism. Once earned, trust must be guarded. If the greater narratives museums present are to be believed, accuracy in all things—to the best of our ability—should be our goal. No detail is too small.

The memory of my mom’s observation has stayed with me throughout my museum career—a constant reminder of the importance of developing skill and understanding process in addition to having the right stuff.

Although I don’t demonstrate historical skills as an interpreter any more, I do obsess over material culture details in my museum projects. When I don’t know, I find someone who does.

Mom isn’t around to comment on my work any more. But that innocent stock photo in a WordPress email brought it all back.

##

Postscript – Most people now call # a hashtag, but in typewriter days, journalists used two “pound signs” centered on the page to indicate the end of the story. Because I have a few postscripts, however, it’s not really the end of the story!

Post Postscript – The typewriter in question is a 1970s Olivetti Linea 98 manual typewriter with a wide carriage, probably 27 inches. I did some searching and found other stock photos of the same typewriter from different angles (see below). No manufacturer name appeared in any of them, so I did what I always do at a dead end: I asked an expert! Thanks to Richard Polt for providing the ID. Here’s a link to his excellent typewriter website.

Post Post-Postscript – Interesting how things come full circle. In addition to her farming knowledge, my mom was an expert typist—80 words a minute on her mid-50s Smith Corona portable—before arthritis robbed her fingers of flexibility. I learned to type on that machine and my sister still has it. I have the 1930 Remington Portable No. 3 that belonged to my dad’s mother. Both still work, although the Remington’s ribbon has dried out. (It was last changed when I was in high school, according to a methodical note on the ribbon box.) An old Dr. West’s toothbrush, used to clean the type was still tucked in the case. In 1938, Dr. West’s was the first brand to adopt nylon bristles, just a year after a Dupont scientist invented nylon. This one has nylon bristles, but because I’m not putting it in an exhibit I didn’t attempt to date the toothbrush. And yes—if I were, I would! It’s all about the details.

Post Post-Post-Postscript – A museum organization that can connect you to experts and teach you skills of bygone eras is the Association for Living History, Farm, and Agricultural Museums (ALHFAM). I’ve been a member since 1985, not long before my mom made her dry observation. And in another instance of things coming full circle, I just saw the call for proposals for ALHFAM’s 2021 Annual Meeting and Conference. The illustration is—you guessed it—an old typewriter! I’m happy to report it does have paper on the carriage.

For real this time:

##

Reflections of a Hillbilly Woman: Remembering Elaine (Burke) Seelhorst

Or, “A-diggin’ in a polecat hole jest ain’t a smart idea.”

One year ago today, November 9, 2018, Elaine Seelhorst died at 6am just as the first snow of the season started to fall. I am one of her three children.

To honor her memory, I’m posting what she called her book: recollections of her childhood in eastern Kentucky where she grew up the oldest of five children. Mom started it when she was about 87, but writing was slow going with her failing eyesight and twisted fingers. It’s really good. I encouraged her to write more, and am sorry I didn’t find the time to help her do it.

This is her title, her asides in brackets, and for the most part her spellings–I just gave it a light edit for consistency. The only thing I added is the alternate “polecat” title of the post, but only to keep you reading until you see what happened!

She was one of those ordinary people who had extraordinary traits. Hers was the ability to get up every day of her 91 years and try to make a difference in her world, even as her physical access to the world kept shrinking.

Mom developed severe rheumatoid arthritis in the early 1960s, when treatments and even diagnoses were hard to come by and not very effective. But even as she became more disabled, she helped educate others about arthritis and successfully lobbied governments to provide handicap access long before the Americans with Disabilities Act mandated it.

She decided to write her book using spellings that suggest the distinctive accent of that area, as her favorite author Jesse Stuart did in some of his books about that area. She later worked to “unlearn” her accent, and for a time had a love/hate relationship with the place of her birth. But in the end, she was proud of where she came from and the traditions and work ethic learned from her parents, Sena and Howard Burke.

We kids glimpsed the remnants of that life as we grew up. At some point after the events described here, they moved down the road to an old 7-room farmhouse with a root cellar, smoke house, tobacco barn, and an outhouse. They used well water and stoked a coal stove for heat. Grandma and Grandpa lived there into the 1980s. It was only torn down a few years ago.

Mom was born in Greenup County. But I’ll let her tell you. Rest in peace, Mom.

Reflections of a Hillbilly Woman

By F. Elaine Burke Seelhorst

January 12, 1927, 11pm. Thu wind was a-howlin’ round corners uf thu log cabin wif snow a-blowin’ betwixt cracks where I’s birthed. Ole Doc Meadows brought me in a-screamin’ like a-wildcat cause I had yeller jaundice.

Mom tried nursin’ but I couldn’t suck. I jest kep a-cryin’. [Mom told me about it many years later.] Next mornin’ Dad took Ole Doc Meadows home ‘n bought Mellon’s Food at thu drug store. Hit was my vittles fer one year or more.

Erwin Lewis Burke was birthed February 1, 1928, in thu three-room house Dad built fer ‘is growin’ fambly on his 50 acres Gran’pa Tobias Burke deeded ‘im.

Thu house was down hill from thu one-lane rutty dirt road. A-risin’ wind jest sent dust a-swirlin’ round thu hill. Hit’s barely wide enough fer a-jolt wagon [farm wagon].

Mom nursed Lewis fer a year. She jest couldn’t hep Dad in thu fields ‘n continue nursin’ Lewis. Tu wean ‘im, she dobbed mud on ‘er breast. Hit shocked ‘im ‘n ‘e quit.

Mom ‘n Dad traded their horses fer two sure-footed mules. Ole Joe was white ‘n Ole Bob was black, both essential fer our survival. When Dad hitched ‘em up tu thu mould-board plow, he put thu reins around ‘is right shoulder ‘n under ‘is left arm. To git ‘em a-movin, he’d say “giddy up.” To turn ‘em right, “gee” ‘n pull reins right, “haw” fer left ‘n pull reins left.

Dad took good ker uf ‘is mules, a-feedin’, waterin’ ‘n a-groomin’ ‘em. I’ve watched Dad remove worn-out horse shoes ‘n trim thu growin’ hoof. He’d heat thy new shoe red hot ‘n re-size hit tu fit thu trimmed hoof.

I’s a-cryin’ ’n a-cryin’. Dad tried tu hep me but my stummick jest hurt. I’s about two so I remember hit.

I’s called “Cotton Top” cause my hair was white.

Mom had tu keer fer me ‘n Lewis while she cooked vittles ‘n tended thu garden. She picked ‘n prepared beans, peas, shucked ‘n biled sweet corn. She made corn bread ‘n strawberry-rhubarb, cherry, or apple pie fer dinner.

High noon, Dad came from creek bottom tu et a lip-smackin’ dinner. Mom ‘n Dad had cheers but Lewis ‘n me had tu stand at thu table tu et.

We didn’t haf a clock, ‘n Dad’s old watch jest wore out. We could tell time by thu sun’s position ‘n thu shadows hit cast.

Mom worked hard a-pickin’ preparin’ ‘n cannin’ food fer winter. She picked sweet corn ‘n green beans. She pickled some uf thu beans ‘n canned ‘em. She canned tomato juice ‘n peaches. She made wild blackberry jam ‘n peach preserves ‘n canned ‘em. All canned food was stored in thu cellar under thu house fer winter.

Cannin’s hard work. Quart-size jars were used fer corn ‘n beans. Jars, zinc lids ‘n rubber sealing rings were sterilized on thu kitchen stove. Thu jars were filled ‘n put in thu big rectangular pot located down-hill on level ground. She put feed sacks betwixt thu jars ‘n covered ‘em wif water. She drew water from thu rock-lined well ‘n toted hit down hill ‘n covered thu jars. She built a fahr under thu pot. Beans ‘n corn had tu be kep a-bilin’ fer four hours. I’s about four years old ‘n Lewis ‘n me hep kep thu fahr a-burnin’.

At age five I washed jars ‘n hepped sterilize ‘em.

Mom shredded cabbage. She sprinkled salt on each layer as she pushed hit in a large, clean feed sack. She tied thu sack ‘n put hit in a size 15/20 crock. A clean, round, ‘eavy rock on top held hit down. Hit was stored in our cellar. [By the way, salt kills bacteria.] She may haf canned thu sour kraut.

In thu fall Dad picked apples ‘n put ‘em in a wooden barrel, sulfered ‘em ‘n stored it in thu smoke house.

Mom an Dad worked hard spring, summer ‘n fall tu haf essential vittles fer fambly, hay ‘n corn fer livestock. Lewis ‘n me hepped when we got older.

Corn was always planted in thu creek bottom. Seed corn was put in box on a “corn jobber” that let one er two seeds go in thu ground. Heavy rain in thu headwaters caused Tygart Creek tu rise ‘n cover thu corn plants. Hit had t’ be re-planted atter thu ground dried out. Hit was hard, back-breakin’ work. Corn was vital fer our survival. Pioneer livin’ ain’t fer faint-hearted folks.

Dad had a-hernia ‘n had tu wear a truss. He worked hard anyway. Dad was deaf too but he could read lips.

Dad mowed hay, racked, stacked hit on jolt-wagon frame. He drove thu mules, Ole Joe ‘n Ole Bob, up thu steep hill tu thu level road all thu way tu thu hand-hewn log barn. Uncle Hobert pitched hay intu thu loft ‘n Dad moved hit back in place.

In late fall, Dad always butchered a big hog. All fat was rendered on thu kitchen stove. Part uf thu meat was ground up, made 1 1/2 inch sausage patties, fried ‘n packed in sterilized quart jars. Bilin’ fat was poured in jars around thu sausage, sealed ‘n stored in cellar. Dad hepped Mom do this fast-paced hot work. We et every part uf thu pig, even ears ‘n tail.

Dad put ham ‘n bacon in thu smoke house ‘n cured hit.

Gran’ma Sarah Jane Newsome-Burke jest didn’t like ‘er new daughter-in-law. She shore changed ‘er mind atter a-seein’ ‘er work beside ‘er man in thu fields.

Ye see, Mom had never worked hard on a farm. Mom’s thu youngest uf seven girls in thu Lewis fambly.

Mom went tu Normal School fer teachers, in Richmond, Kentucky. Dad went tu Normal School fer teachers in Morehead, Kentucky.

Mom moved tu Greenup County tu teach in a-two-room school where she met Dad. ‘E had a Chevy car ‘n went home atter school was out. Mom had tu board wif a nearby fambly. Mom traveled on ‘er horse. All thu Lewis fambly rode horses ‘n tuck good keer of ‘em.

Mom ‘n Dad married December 24, 1925.

Mom ast Gran’ma tu keer fer me an Lewis fer a-few days.

Gran’ma had picked a-bucketful uf wild blackberries. Thu Burke’s love pickin’ wild blackberries etin’ ‘em, cannin’ ‘n makin’ jelly ‘n jam, tu store in cellars fer winter etin’.

“Jest don’t give Cotton Top blackberries tu et cause she’ll git a-runnin’ off cause she has stummick trouble. Lewis can et some uf ‘em,” Mom said.

News came Ant Minnie Evans’ new house had burned. Thu fambily moved back intu thu dog-trot log house. Mom ‘n Dad ‘n all fambily members shared belongings wif Ant Minnie.

Ant Allie an Uncle Millard Lewis took me an Lewis home wif ‘em. Uncle Millard had a bigger car ‘n Dad’s. We shore liked a-ridin’ in thu back seat. Thu snow was deep but Uncle Millard did git home.

“Ant Allie yer house is real perty. Ye haf a-big front porch. In summer ye can sit tu see yer friends a-drivin’ by,” I said.

“Hits bigger ’n our house,” Lewis said. “Ye gotta a livin’ room wif a big davenport an three easy-sittin’ chears.”

“Oh! Ant Allie, ye gotta room wif a big table an cheers a-round hit,” I said.

“Hits a dinin’ room, where we et,” she said.

“We et in our kitchen a-standin’ up at thu table.” Lewis said.

“Ant Allie, ye haf two bedrooms,” Lewis said, as he bounced on one uf ‘em an messed up thu counterpane.

“Hit will be yer bed,” Ant Allie said.

Ant Allie had a big kitchen wif a sink. Hit had runnin’ water! We didn’t haf runnin’ water in our sink. We carried water from thu well. She had a-room next tu thu kitchen. Hit had a bathin’ tub.

“At home we git a bath in thu wash tub in our kitchen,” I said.

Ant Allie had a woman wash their clothes wif a washboard. She hangs ‘em on a clothes line tu dry an irons ‘em wif a-flat iron heated on kitchen stove.

“Hits hard work,” I said. “Mom has a-washer woman. She carries well-water downhill tu fill a-large iron kettle ‘n builds a-fahre tu bile thu water. She uses lye soap Mom makes tu clean dirty clothes.”

“Uncle Millard, I like y’er back porch don’t haf a roof,” Lewis said, as he rolled an rolled in thu snow. He got up lookin’ a-lettle bit like a snow man. Uncle Millard laughed an brushed thu snow clean off. He was real good tu Lewis.

We shore liked Ant Allie’s vittles cause they’re better ’n vittles we haf at home.

Ant Allie gave us a-job dustin’ thu furniture. We shore made hit shine.

Uncle Millard was a-givin’ Lewis a-bath.

“Allie, I jest cain’t git Lewis clean. I’ve scrubbed an scrubbed,” he said.

“Oh Millard! He’s clean cause he didn’t wear a shirt last summer an he got real brown,” Ant Allie said.

We stayed wif Ant Allie an Uncle Millard fer a long time. We shore liked a-livin’ wif ‘em. They liked us.

“Hits time fer ye tu go home,” Ant Allie said. Ant Allie an Uncle Millard was so good tu us we ast tu stay wif ‘em.

“No, cause yer Mom an Dad want ye tu come home,” Ant Allie said. She put one uf ‘er counterpanes in a special sack fer us tu give Mom.

Thu snow was deep but Uncle Millard’s big car did git us home.

Dad opened thu door fer us. We saw Mom a-sittin’ in thu chear a-holdin’ a wrapped up bundle.

“Mom, yer holdin’ somethin’. What is hit?” I ast.

Mom showed us a baby.

“Mary Jane is yer baby sister come tu live wif us,” she said.

“Mom, how did she git here? Why didn’t ye tell Lewis an me ye was bringin’ a baby?” I ast.

Mom jest didn’t answer. Dad was quiet too.

Ant Allie didn’t say a word. She took thu baby from Mom, kissed ‘er an walked tu thu kitchen a-talkin’ tu ‘er. She came back, handed Mom thu baby. She gave Mom thu counterpane fer ‘er bed. Mom was so glad tu get hit.

Ant Allie an Uncle Millard left fer home cause thu snow was gittin’ deep.

Mary Jane Burke was birthed January 18th, 1930.

Thu snow was real deep. Hit covered thu fruit trees around thu house. Thu world looked clean an bright.

Mom gave ‘er clean dishpan tu Dad an ast im tu git clean snow in hit. She stirred in cream an sugar. She called hit snow cream. Hit shore was good. Mom always made snow cream every winter when snow was deep an clean.

Lewis an me watched Dad shovel snow tu thu well an all thu buildin’s. After feedin’ cows an mules he led ‘em tu thu water tank an broke thu ice. They emptied thu tank an Dad had tu draw more water from thu well. Dad an thu animals went back in thu barn. He milked thu cows an gave thu barn cats some. He brought a large bucket uf warm-foamy milk tu thu house. Hit was cold hard work that had tu be done. Dad was real strong an had always worked hard. Pioneer farming ain’t fer faint-hearted folks.

Mom always strained thu milk an put hit in a big crock tu let cream rise. A lettle uf thu heaviest cream was skinned off an thu milk was poured in Mom’s churn. When hit was ready she churned thu milk an cream intu butter. We drank delicious buttermilk. Mom made cat heads [biscuits] an’ corn bread wif hit. She pressed butter intu a mold. In warm weather thu butter was put in buckets an lowered in thu water well tu cool. Hit was taken tu thu grocery store an sold or traded fer items Mom or Dad needed.

Our livin’ room had a stove that burned wood tu keep us warm but hit would be cold at night if thu fire went out. Mom’s cook stove was at thu far end uf thu kitchen.

Mom ast Gran’ma Burke tu keer fer Mary Jane while she hepped Dad plant corn.

Lewis an me were a-sittin’ on a pallet under a tree next tu Reuben Potter’s fence where Mom had left us. Hit was fur above thu creek bottom where they worked.

Lewis an me saw a man a-walkin’ down thu jolt wagon-sized long road. He had a long silky-white beard.

“I’m yer Gran’pa Lewis,” he said.

He picked us up wif hugs an kisses. I pulled ‘is beard. He didn’t mind cause he jest laughed. I fell in love wif ‘im cause he liked us. We needed to be loved by our Gran’pa Lewis.

Mom looked up, saw ‘er dad an ran back up thu long hill tu greet ‘im.

Gran’pa Elisha M. Lewis rode ‘is horse a-fur piece from ‘is home on Horton Flats at Bruin, Kentucky. Gran’pa had two hickory-bark-bottom chears he made fer Lewis an me. [I still have one of them.]

Gran’pa took keer uf us while Mom an Dad finished a-plantin’ corn. Gran’pa Lewis told us stories an played games wif us. Hide-an-seek was our favorite. We shore wished he could live closer tu us so we could visit wif ‘im.

Sunday mornin’ Mom an Grand’pa took us tu-meetin’ wif ‘em at Mount Olive Church jest down thu road a-piece. Atter a-while Lewis jest had tu go. “Mom, ken I go pee?” he ast.

“Yep,” Mom said.

Thu Regular Baptist preacher said, ”Praise God all ye sinners.” Suddenly, a lettle voice was heard outside.

“Glory be tu God all ye sinners! Praise God!”

Hit was Lewis! He repeated hit as h’ ran around thu church. He was a-runnin’ fast as ’is lettle legs could carry ’im around thu church buildin’. Mom jumped up tu go git ‘im. She ketched ‘im as he reached thu corner.

Atter laughter died down, thu preacher said, “Ye’ll be a preacher some day.” He finished ‘is sermon askin’ sinners tu come forward. Nary a one jined thu church.

Thu preacher an choir are on a-raised platform. Thu preacher stands in thu middle wif a stand fer ‘is Bible. There’s two rows uf benches on ‘is left fer men an two rows uf benches on ‘is right fer ladies. Thu men’s leader stands up an “lines” thu first line uf thu song. Thu choir “surges” that line uf thu song. Each line is spoken an hit is surged until thu song is complete. Usually hits a beautiful mournful sound.

Thu Preacher closed wif a prayer. Folks shook neighbor’s hands an slowly left fer home.

Young men were a-hangin’ around outside thu church. I s’pect they wanted tu ketch thu eye uf a-perty gal.

Next mornin’, a-fore sun peeped over thu east hill an dew had laid thu dust, Gran’pa kissed us goodbye. He saddled ‘is black horse an headed south fer home wif us a-wavin’ bye ‘til he was out uf sight.

We never saw ‘im again. H’ died wif kidney infection in 1931.

Lewis an me never wore shoes during spring, summer an late fall. Our feet would get awful cold early mornin’ when we had tu bring Ole Betty an Ole Jersey from pasture to be milked. Lewis was so cold, he would lie down where Ole Betty got up tu git warm. I would stand on Ole Jersey’s spot to warm.

Mom liked tu cook. She liked makin’ vittles fer us tu et. She was always a-singin’ thu Baptist songs she loved as she cooked. Fer breakfast she baked cat heads [biscuits], sliced ham from thu smoke house, an red-eye sop [gravy]. Dad liked bacon an fried eggs cause he worked very hard. They sold thu eggs cause they needed thu money.

Dad ordered baby chicks. They came tu thu post office in a big box. He bought a brooder tu kep ‘em warm, fed an watered ‘em til big enough tu turn loose in a woven-wire fence chicken yard. He fed an watered ‘em til they grew tu fryer size. Mom an Dad dressed ‘em fer market. He got good price fer ‘is plump fryers. Some uf thu chickens grew up tu lay eggs. We had fried chicken too.

I kep a-hearin’ ‘em talk about a depression. I didn’t know what hit was. I reckend hit meant money tu buy things. Hit was hard tu git.

“Mom, what’s thu big bird wif two wings a-flyin’ over thu hills. Hits got a loud ugly song. Hit ain’t a bit perty like all our other birds.”

“Oh, Cotton, hits not a-bird. Hits a airplane wif government men a-lookin’ fer stills. They’re Revenours a-lookin fer smoke a-risin’ above thu trees tu ketch men a-makin hooch,” she said.

Lewis an me went a-lookin’ fer guys a-makin’ hooch ‘cause thu airplane flew over our hill. We had trouble a-climbin’ thu hill. Hit was wet an slippery cause uf a chunk-washer. [Heavy rain]

We walked across thu hill tu Uncle Walter’s farm. He rented thu cabin I’s birthed in tu ‘is friend.

“Lewis, do ye hear talkin’?” I ast.

“Yep,” he said.

We laid down on slippery leaves so we wouldn’t fall over thu hill. Wigglin’ tu thu edge we peeped over an saw two guys wif a fahr under a barrel. Branch water ran down to it.

“Hits shore funny lookin’,” I said.

“Cotton, let’s mess their water,” Lewis said.

Our bare feet did hit. We peeped over an watched muddy water run down thu branch. Thu two guys came a-lookin’ fer us, a-cussin an a-runnin’ a blue streak. We ran home a-slippin’ an a-sliddin’ down thu hill tu home. We got wet an muddy.

We told Dad did what we did.

“Hit was dangerous! Don’t go a-lookin’ fer any more men a-makin’ hooch,” he said. Uncle Walter lost ‘is renter.

Gran’pa Tobias Burke got a farm on Grays Branch, Kentucky. Hit was a big well-built house that faced Route 23. Hit had a big barn, a smoke house on top uf a cellar, a coal house an a big garden an lots uf fruit trees. Best of all it had a giverment-built privy a long way from thu house.

A large built-up railroad was about a half-mile north an they could see large coal an passenger trains a-rollin’ by whenever they had time to sit on thu front porch in summer. They could see thu Ohio hills, but they couldn’t see thu Ohio River cause thu built-up railroad tracks hid thu view.

Mom, Dad, an Uncle Hobart hepped Gran’ma an Gran’pa move. Hit was a-lot uf hard work. Mom cleaned thu home place atter hit was emptied.

Atter he moved, Gran’pa rented thu home place tu folks named Butler an Marian Bleu. Mr. Bleu worked thu night shift at Wheeling Steel in New Boston, Ohio.

“Will you let Elaine stay with me at night because I’m a little afraid to be alone?” Mrs. Marian asked Mom.

“I’ll let ‘er but ye must walk her home when Butler comes home early,” Mom said.

I shore liked stayin’ wif ‘er. Mrs. Marian was so good tu me. I et store-bought vittles wif ‘er.

“Hit ain’t like thu vittles we et at home,” I said.

Mrs. Marian was real good tu me. I liked stayin’ wif her.

Mrs. Marian gave me a perty doll. Hit was stuffed wif straw. She bought toys fer all of us. We only had homemade wood-stick toys.

Mrs. Marian asked Mom tu let her adopt me. Mom said, “No, we need ‘er at home.”

Mom an Dad let me go wif Mr. an Mrs. Bleu to the Wheeling Steel Union Rally in New Boston, Ohio. Hit was a loud, noisy place an some guys got real mean an fought wif each other.

Mrs. Marian moved away from ‘em an bought hot dogs an pop. Hit shore was different vittles. Atter thu rally was over we went home.

Lewis wanted tu hear all about the rally an I ‘splained hit tu ‘im. “Gosh, why did they fight?” he ast.

“They yelled, ‘Yeller Dogs!’ an started a-hittin’ ‘em,” I said.

Thu sun set beyond thu creek against thu western hill castin’ a reddish-yellow glow back tu me. I liked tu sit on thu lettle back porch an listen tu night sound as dusk descended. Hit was music tu my ears. Thu screech owls, thu hoot hoot hoot uf big owls. I loved a night bird singin’ “Un-cle Rip, Un-cle Rip” as hit called tu others. Thu possum a-scramblin’ up thu bank wif ‘er babies on ‘er back. Bats flyin’ tu catch insects. Crickets a-calln’ an lettle frogs a-peepin’ in thu ditch above thu road.

First time I heard “Un-cle Rip,” I went back in thu house an said, “Mom, hit says “Un-cle Rip, Un-cle Rip.”

“Yes,” she said, “Hit’s a Whip-por-will.” I never did see one uf ‘em cause they’re shy evening ground birds

Uncle Hobert’s fifty acres was north uf Dads. Uncle Hobert was married tu Myrtle Potter. Ant Myrtle had a new baby about every year. He was a happy man. I remember Loretta an Fred. They had so many youngins I can’t recall thu names.

‘Is house overlooked Dad’s creek bottom. We could look up thu bank an see our cousins a-playin’ in thu front yard.

Uncle Hobert had several foxhounds. ‘E hunted fox wif others every Saturday night. I loved tu hear hunters’ horns a-blowin’. Thu dogs could be told what tu do by their master’s horn. They ain’t perty dogs but they shore are smart.

News came that Gran’pa Lewis had died. Hit gest broke our hearts. Our fambly, and Ants Allie, Hattie, and Bertha, went tu ‘is Horton Flats home as fast we could. We met Gran’ma Sarah Jane Johnson Lewis cried an cried wif grief.

Gran’pa was on ‘is bed. A white cloth covered ‘is face.

I went wif my cousins tu git old-fashioned roses tu put a-top ‘is wooden coffin.

Neighbors had built ‘is coffin an dug ‘is grave. Thu bottom an all four sides uf thu grave were lined wif logs.

Thu Baptist choir sang Gran’pa’s favorite hymns. Thu preacher said thu last words ever uttered fer Gran’pa Lewis.

Men used their horses’ check lines tu lower Gran’pa’s coffin in thu grave. After kinfolks left they filled thu grave. They tamped thu earth down. We went back later and covered Gran’pa’s grave wif roses.

Gran’ma Lewis went home wif Ant Ally. They went back later. Thu farm was sold an plunder divided or sold.

Ant Marj sent Mom Ladies Home Journal. She was Col. Jack Burke’s wife. They lived in Buffalo, New York. They had two sons, Toby an Eddie. Ant Marj sent us clothes ‘er boys outgrew. She sent other things too. Ant Marj was a beautiful kind lady.

Dad’s footlocker was between our beds. I was curious.

I said tu Lewis, “Hep me open hit.”

We found a rolled up rubber thang. “Hits a balloon,” I said. After unrollin’ we tried a-blowin’ hit up but we couldn’t.

“We better put hit back jest like hit was cause Dad would git mad.” I said. We closed thu footlocker ’n left.

Mom had a Singer pedal-powered sewing machine. She made feed-sack dresses an bloomers fur me an white shirts fur Lewis. Mom never used a pattern but she had newspapers tu cut patterns tu fit. Hit’s jest natural fur ‘er. She made a perty pink sack dress fur me.

We went a-visitin’ Ant Bertha Riggs, ‘er rich sister.

Mom said, “Don’t tell ‘em hit’s made outta feed sacks. Hit’ll be our secret.”

I marched right in showin’ off my purty-pink dress ‘n said, “See my purty feed-sack dress!”

My three cousins doubled-up a-laughin’. I cried.

Ant Bertha sent ‘em tu their rooms. They had separate rooms ‘n beds were kivered wif counterpanes.

Our family had one bedroom wif a double bed fur Mom an Dad. Lewis an me had thu other ‘un. We had a feather bed on top uf bed-size sacks filled wif corn-husks that laid on boards. The outer cornhusks were disposed uf. Husk next tu thu corn was saved fer our beds.

Mom was always a-singin’ religious songs while she cooked our vittles. She could whip-up cat heads faster’en most any woman. Men never cooked ‘cause hits woman’s work! Mighty strange! Women worked in thu fields wif thu men but hit wasn’t called men’s work.

Me and Lewis went bare footed from early spring ‘til frost. Dad didn’t haf money tu buy summer shoes. Our shoes came from second stores.

Barefoot Lewis and ‘is dog, Ole Bowser, was jest a-strollin’ in the meader a-tryin’ tu stay away from green briars. Suddenly, Bowser started a-diggin’ in a hole. Lewis hepped ‘im dig. Dirt was a-pillin’ up, and all uf a-sudden a Polecat let go wif a blast. Lewis and Ole Bowser ran fur their lives wif stingin’ eyes and smellin’ like a Polecat.

Mom bathed Lewis with tomato juice. Ole Bowser crawled under thu house but we rolled ‘im outen there an ’e got a-tomato juicn’ too. Mom doctored Lewis’s scratched feet. She buried ‘is clothes in thu ground fur four days ‘til thu smell left.

“Lewis, a-diggin’ in a polecat hole jest ain’t a smart idea,” Dad said.

(c) 2018 F. E. Seelhorst

What Happened While I Was Gone: Remembering Tony Swan

I haven’t posted here in several years. Not that anyone would notice—I don’t post for clicks and I don’t have a lot of followers. But when people land here, especially those who might be considering whether to hire me, I like to have a relatively recent post about museums, history, or culture if for no other reason than to prove I’m alive and am keeping the site up to date.

It’s a little embarrassing that my last post was more than three years ago. My excuse is that in January of 2016, my husband (auto journalist Tony Swan) discovered that his head and neck cancer had returned for the fourth or fifth time (I lost count) and this time had migrated to a lung. I quit my band, reduced my workload, and focused on helping him through his treatments and pick off bucket list items. I also helped my mother as she repeatedly cycled between the hospital, rehab, and a nursing home near me in 2017 and 2018.

So, I let this blog—a modest outlet for the exercise of my essay-writing muscles—atrophy for awhile. Today seems like a good day to revive it.

Tony died one year ago today, September 27, 2018, at 11:45pm. My mother died a few weeks later, November 6, 2018 at age 91. She was a remarkable person as well, but since my last post was about my ex-husband after his death, it’s only fair I write about Tony this time. I’ll write about my mom next post.

I’ve written a lot about Tony already for other purposes, and his automotive journalism colleagues wrote kindly about him after his death. (Car and Driver, Detroit Free Press, Motor Trend, Minneapolis Star Tribune, The Detroit Bureau and, perhaps my favorite, The Drive.)

One year out, what do I say that hasn’t been said? My blog is nominally about history, so I’ll look at his relationship with history instead of rehashing Tony’s adventures—things like press trips, auto racing, visiting friends, encouraging colleagues, reading every day, and always, always writing—even in doctor’s waiting rooms—up to two weeks before he died.

Tony was a history major at University of Minnesota, with a minor in journalism. His bookcases were lined with history titles—all of which he actually read and most of which he remembered. Luckily for me, he loved to visit museums and historic sites of all kinds, often giving tour guides a pleasant surprise with his excellent questions informed by prior reading. His stories—even reviews of new cars—were spiced with historical references that grounded his readers in the long view.

One of the things I miss most, next to hugs and the excellent coffee he made every morning, was exchanging our drafts and reading each others’ work. It was always a great conversation. We’d ask questions, clarify details, check facts, and generally make each others’ work better.

While I could go on at length, this is a blog post, not a book. I’ll finish with the last thing Tony read: Winston Churchill’s 6-volume set The Second World War. He picked away at it all year. Two weeks before he died, we ended up in the ER and then in intensive care at the Mayo Clinic when he started to bleed out on our drive home from his hometown of Mound, Minnesota. (That often happens with head-and-neck cancer patients in late stages.) When he got to a room, he didn’t want his laptop or his phone—he wanted Churchill’s Volume 6, so he could finish it. He knew he wasn’t long for this world. But still he wanted to read history.

He was an atheist, and didn’t believe in a religious afterlife. While Tony never put it in words, I think studying history gave him confidence in a sort of intellectual afterlife: he could pass away knowing that he, like all of us, would be part of the slipstream of history.

Since Tony’s death, hearing and reading the many tributes of his colleagues led me to realize that perhaps his best contribution to the slipstream of history was helping and inspiring other journalists to do these three things: know their history, give honest opinions, and continue educating themselves. Tony, like all of us, was far from perfect, but he was able and willing to grow and evolve throughout his life. I admire that.

He didn’t want to fade away, and he found a way not to. I hope I can do the same.

Drive fast, take chances.

I miss you Tony.

How to Live History: Remembering Blake Hayes

I returned home last night from the party held in memory of Blake Hayes in Cherry Valley, New York. This post is a bit unusual in that it’s written for colleagues in the museum field, the line of work to which Blake dedicated his life—especially for members of the Association for Living History, Farm, and Agricultural Museums (ALHFAM).

I met Blake at ALHFAM’s annual conference in 1986. We got married and were together 15 years before we moved on personally, but we remained engaged professionally and as friends. (Don’t worry, Blake and his wife Lorraine and me and my husband Tony all get along!)

His memorial party was an amazing event, with his friends from childhood, high school and college, his immediate family, adopted family, extended family (I think there were even in-laws of in-laws there!), “ex-family” (still regarded as family), professional colleagues, neighbors, local and regional friends, kids who grew up around him and brought their own kids, ALHFAM colleagues, Jell-O shots (which no one understood except the ALHFAMers), pets, meats, and music.

I heard Katie Boardman, one of Blake’s partners at the Cherry Valley Group, say that the comments and tributes to Blake “broke the ALHFAM-L,” a professional listserv normally used for questions and comments about museum matters. I think they also broke Facebook. After not checking my inbox for three days, I discovered literally hundreds of unread emails, nearly all Facebook notifications, ALHFAM-L summaries or personal messages about Blake.

This electronic outpouring, however, made me realize that as much of a tech enthusiast as he was, Blake didn’t need social media. He was social in the old-fashioned way—in person. He met, called, welcomed, taught, partied, shared time and stories, food and drink. Even when he was arguing his point of view passionately, it wasn’t personal. Even when he couldn’t type or walk any more, he talked. As his family reported, it was when he stopped talking that they knew the end was near.

Almost the only thing he didn’t share widely was news of his illness.

While we miss and remember and treasure all of our departed ALHFAM colleagues, I think it was Blake’s extremely social nature and long-term, deep commitment to ALHFAM that has made him so profoundly missed by all of us. Wherever Blake was, the party was. But when the party was over, valuable teaching and learning and doing occurred, informed and enhanced by personal relationships. Blake’s life is a reminder that opinionated doesn’t have to mean obnoxious.

As Dr. Takuji Doi, a long-departed ALHFAM colleague from Japan, once said after observing the flow of the annual meeting: “The difference between Japan and America: In Japan, make big decision, get drunk. In America, get drunk, make big decision!”

We need to continue to tell all of ALHFAM’s stories, the jokes, and the memories. And as much as possible we need to do it in person. There is no real substitute that can perpetuate our history. Maintaining the folklore of this organization and of your sites depends on you.

So go to your regional meetings, or those of other regions. Attend the annual conference whenever you can. Show up for your local history-related events. Gather with colleagues after hours for meals. Do it in memory of all our dearly departed, do it for yourself, and do it for the next generation.

Telling stories is, after all, the essence of history.

I recently came across something that, to me at least, seems to embody Blake’s professional and personal philosophy. It’s the last paragraph of Will and Ariel Durant’s book, The Lessons of History, published in 1968 (the year Blake graduated from high school).

To those of us who study history not merely as a warning reminder of man’s follies and crimes, but also as an encouraging remembrance of generative souls, the past ceases to be a depressing chamber of horrors; it becomes a celestial city, a spacious country of the mind, wherein a thousand saints, statesmen, inventors, scientists, poets, artists, musicians, lovers, and philosophers still live and speak, teach and carve and sing. The historian will not mourn because he can see no meaning in human existence except that which man puts into it; let it be our pride that we ourselves may put meaning into our lives, and sometimes a significance that transcends death. If a man is fortunate he will, before he dies, gather up as much as he can of his civilized heritage and transmit it to his children. And to his final breath he will be grateful for this inexhaustible legacy, knowing that it is our nourishing mother and our lasting life.

May Blake live long in that spacious country of our minds, building and organizing, cooking and joking, helping and sharing. With much love always, ms

(Thanks to Eileen Hook for this great 2013 photo of Blake going Full Woodstock at ALHFAM!)

NTS+GUI=HGH+AVT=YOD+BIS (WTF?): Neal Stephenson and Me

I’ve been a fan of sci-fi-cyberpunk-whatever-you-call-it-or-him author Neal Town Stephenson for years—well, decades actually. From back when he had hair. (No, I’m not trying to insult him even though I probably just did. I’m a few months older than he is, and besides, I think he shaves his head.)

(BTW, the title of this post is a lame attempt at doing a Neal Stephenson-style title. Eventually, if you care to try, you might figure it out. I tried using some HTML symbols in it, but Word Press wanted to read it as actual HTML. It got weird. But no weirder than my love of parenthetical asides.)

I first became aware of him sometime in the mid-1990s through one of his articles in Wired. I kept a few, the oldest a 1994 issue that included “Spew,” a short story that today I’d describe as The Matrix meets Hee Haw. (Now that I think of it, The Matrix would have been more fun with a few Buck Owens types. Imagine if The Oracle turned out to be Minnie Pearl!)

Whenever I look back at Stephenson’s older works I invariably find a passage which has new resonance with me. For instance, if I changed “guy” to “gal,” I could have written the first sentence of “Spew” about myself today:

Yeah, I know it’s boring of me to send you plain old Text like this, and I hope you don’t just blow this message off without reading it. But what can I say, I was an English major. On video, I come off like a stunned bystander. I’m just a Text kind of guy.

Video is massively more important today than in 1994, but I’m still a video voyeur. I’ll view it, I’ll shoot it, but I don’t want to be in it. (I’m a Twitter voyeur too, but that’s another story.)

In keeping with my habit taking a fresh look at Neal’s old works, I cracked open the slim non-fiction paperback, In the Beginning was the Command Line, his 1999 analysis of the state of computing back when the Mac v Windows debate actually mattered. (“Cracked open” is not a cliché in this case. The book was so brittle the binding literally cracked.) It was published in that short span of time after all the other commercial operating systems had flamed out and the era of the mobile device had not yet dawned. (Yes, Linux was around, but A, it’s free, and B, it was only used by serious nerds. Some things never change.)

It was fun to re-read Stephenson’s take on the relationship between computers, their users, and their designers and coders and think about our first home computer (an Osborne “portable” with a CPM operating system), or recall that first magical mouse moment (complete with phantom wrist pain).

But then I read a paragraph that instantly—in my head, anyway—became a dead-on analogy between early developments in computer operating systems and today’s Next Big Thing in automotive engineering: the drive-by-wire-on-human-growth-hormone known as the autonomous vehicle. Maybe someday it’ll make cars safer. But will cars still be fun? I doubt it. Makes me want to hang on to my 2003 Mini Cooper S with the John Cooper Works performance package. No USB port, but on the upside no snoopy black boxes or mommy-car helpers either.

Anyway, I’ve been thinking a lot about Autonomous Vehicle Technology (AVT) lately.

So here’s Stephenson on the graphical user interface, or GUI—all the graphics and images and icons that mask the zeroes and ones that comprise the code running the machine:

The introduction of the Mac triggered a sort of holy war in the computer world. Were GUIs a brilliant design innovation that made computers more human-centered and therefore accessible to the masses, leading us toward an unprecedented revolution in human society, or an insulting bit of audiovisual gimcrackery dreamed up by flaky Bay Area hacker types that stripped computers of their power and flexibility and turned the noble and serious work of computing into a childish video game?

With apologies to Stephenson, here’s my automotive analog:

The introduction of autonomous vehicles triggered a sort of holy war in the automotive world. Was autonomous driving a brilliant design innovation that made vehicles more practical and therefore safer for the masses, leading us toward an unprecedented revolution in human mobility, or an insulting bit of drive-by-wire gimcrackery dreamed up by ambitious Bay Area corporations and embraced by Detroit, et al, that stripped automobiles of the power of human-machine interface and turned the noble and serious work of driving into a childish video game—sans joystick?

I had never before thought of the increasing digitization of the automobile/driver interface as a GUI, but it pretty much is. Although there is an irreducible number of mechanical interfaces required to move a mass of metal, plastic, rubber, and glass down the road, there is no longer any such restriction in the cockpit. With an autonomous vehicle, no mechanical interface is required to start and control the vehicle, other than perhaps Butt in Seat (AKA BIS).

BIS was the same AVT once enjoyed by drunks in Ye Olden Days (YOD), when Old Dobbin waiting patiently outside the tavern could be relied upon to know the way home no matter what state his owner was in.

In YOD horse/rider interface code, the program might read:

Butt in Saddle Home Dobbin! Run End

In the 21st century however, the fact that your ride has a brain (virtual or actual) won’t get your DUI charges dropped. I recently saw a news item about a guy in Louisiana who got pulled over and ticketed for riding his horse under the influence (would that be an RUI?). (For some reason this reminds me of when my horse-avoiding husband—auto journalist Tony Swan—said to a horse-owning friend, “I refuse to drive anything with its own brain,” to which our friend said “Have I got the horse for you!”)

So after all this appropriation and misapplication of Neal Stephenson’s genius, this is the only semi-profound thing I came up with: did it ever occur to you that the abbreviation for “Neal Town Stephenson’s Books” is NTSB, AKA the National Transportation Safety Board? No, I’ll bet it did not.

(A belated postscript: Someone asked me to help decipher the title of this post, and when I revisited it I realized I’d forgotten what HGH stood for and it took me 10 minutes to find it in the text! So here it is: Neal Town Stephenson plus Graphical User Interface equals Human Growth Hormone plus Autonomous Vehicle Technology equals Ye Olden Days plus Butt in Seat.)

Big Sound: Les Paul the Innovator

I was thrilled to have an opportunity to combine my personal and professional interests in music, the history of technology, and exhibit development in one great project: Les Paul’s Big Sound Experience. Its run will soon come to an end, but its a project I’ll never forget. Les was talented, humble, innovative in the truest sense of the word. He was an entertainer and a teacher who prioritized helping others the way he had been helped. While I wish I had known him, through this project I feel like I do.

I was honored to work with people at the Les Paul Foundation who knew Les and the designers and developers at MRA to help bring this project to life with research, scripting, and concept development.

1830s Doctor’s Office Creates Indelible Memories

Last year I was surprised when Tom Woods, director of Hawaiian Mission Houses Historic Site in Honolulu, asked me to create and execute a furnishings plan for an 1830s doctor’s office and storeroom. I knew nothing about the history of medicine or the physical manifestations of medical practice in the 1830s—let alone how a practice in Hawaii might have been different from a practice on the mainland. And the doctor in question was Dr. Gerrit Judd, a well-known figure in Hawaii’s history. But Tom assured me there was a lot of detailed primary source material, and I’d be working with people who did know a lot of that information. Besides, he said, we had plenty of colleagues in ALHFAM (the Association of Living History, Farm, and Agricultural Museums) who could assist with answering questions, pointing me in the right direction, and suggesting sources for reproductions.

And boy did they. Just on my end I worked with at least 14 craftspeople and historians, plus countless vendors of reproduction wares whose knowledge proved invaluable. That’s not even counting those in Hawaii, whose work was managed by the HMH staff. Unfortunately I only got to travel there once to do my portion of the installation, which was finished by the staff after I left. But I hope to return and see the finished product! They’ve produced this great video that shows a lot of furnishing details.

Since I had to leave before the installation was complete, it was exciting for me to see the custom items in context, such as handblown glass, pottery, tinware, a surgical instrument case, crates and barrels, handwritten labels, reproduction medical books—including one written and illustrated by Dr. Judd himself in the Hawaiian language, tracts and educational pamphlets, copper canisters, etc. In addition to the custom orders, I bought many historically appropriate items on eBay, such as apothecary scales, mortar and pestle, glass funnels, tools, etc. Then there were newly manufactured historical items we purchased from vendors–rope, shoes, kitchenware, fabrics.

I was pretty sure the rich and evocative new installation would create an indelible memories for all involved. But literally indelible? For future interpretive and furnishings plans I now have a new item to add to the list of desired visitor outcomes: historically-themed tattoos!

Q: How do you win a one-minute-story writing contest?

A: Take more than one minute to write it.

Depending on where you put the hyphens, it could be writing a story in a minute, or writing a story that can be read in a minute. This was the later. I won’t analyze the possible hyphen permutations now, although it’s a fun exercise if you’re a grammar geek.

Along with two other Michiganders (I reluctantly have to call myself that now, since I’ve lived here for almost 28 years!), I was honored to be selected as one of three winners of the Michigan Radio story-writing contest. Out of 175 entries, that’s not too bad.

The rules specified no more than 120 words—about what can be read in a minute. A friend suggested I enter. He thought my experience writing museum exhibit labels might be helpful. In fact, when I heard I had 120 words, I was thrilled. That’s almost twice as much as I have for most exhibit labels!

The occasion for the contest was the Michigan Humanities Council “Great Michigan Read,” a statewide program focusing on a book about, or written by, a Michigan author. Schools, book clubs, libraries, and other groups participate in readings, author discussions, etc. over the course of two years. The winners of the radio contest were selected in time for the finale event of the Great Michigan Read. The winners were invited, and in addition to good food and great beer, we got signed copies of the featured book, Annie’s Ghosts: A Journey Into a Family Secret by Steve Luxenberg. (If I’d known about it earlier, I’d have suggested a traveling exhibit to go along with the program. Maybe next time!)

The book provided the theme for the radio contest: “Hidden branches of your family tree: Unexpected stories that changed the way you think of yourself or your family.” Steve Luxenberg is an editor at the Washington Post. He read our winning stories at the event, noting that his journalists often turn in lengthy stories with this apology: “Sorry it’s so long; I didn’t have time to write it short.”

Of course Steve is right. When I’m bidding on an exhibit label writing project, I’m always reluctant to offer per-word pricing. You have to learn as much as possible about the subject, much of which will never make it into the label. But in order to choose which bits would make the best label, you have to have all the bits in your head. Then you have to focus on the most intriguing part of the story, and chose every word for maximum information and impact. Often that means editing it several times.

I thought it was interesting that all the winning stories set up the tale, but didn’t try to complete it. They tell about the moment of discovery with no attempt to fill in the blanks. The reader wants to know more.

My trick is to read it out loud before declaring a label complete. So the idea that these short stories would be read on the radio was intriguing. I’ll admit I was disappointed with the way it was read/recorded for the show. But I’ll link to it anyway, and print it below. My disappointment made me remember how critical an actor’s craft is to the success of a play or a movie. I read a lot of Shakespeare starting in 6th grade, but soon discovered that reading a play and seeing good actors perform it were entirely different experiences. The nuance, emphasis, timing, and gestures added meanings I never imagined.

I’ve been wanting to write some of our nutty old family tales for years, but I could never decide if they should be histories, fictionalized novels, songs, poems, or short stories. Well, I now have a start, thanks to Michigan Radio!

The Revelation

Portsmouth Ohio, 1951. Walking with his new wife, my father watched an older man shuffling toward them. As they drew closer, he saw a face partially paralyzed, tragic eyes, trembling hands. “Poor bastard,” he thought. “I wonder what happened to him.”

Suddenly his wife drew up stiffly. “Uncle Noah! It’s been so long since I’ve seen you!” They spoke quietly—pleasantries mostly—then Uncle Noah limped on. Uncle Jack. Uncle Hobart. But Uncle Noah?

Before he could ask, the woman who became my mother leaned toward him, eyes straight ahead, voice low. “They never did get the bullet out of his brain.” As if it were normal. As if he knew what had happened. And why.