I didn’t intend for the theme of my history blog to evolve into “remembering dead relatives.” But without stories about dead people, there would be no history. And the planets keep aligning in ways too relevant to ignore. I’m not even including tonight’s uber-rare conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn, which I won’t be able to see because it’s winter in Michigan. The clouds haven’t lifted all week.

Today’s alignment: this year’s winter solstice marks the 20th anniversary of my dad’s death—December 21, 2000—and it comes as the world’s most massive public health effort gets underway in earnest: administering the Covid-19 vaccine globally. This after the previous massive public health effort—persuading everyone on the planet to wear a mask—failed. At least here in the US.

My dad made a career in public health. Looking back, it’s easy to see why.

His father, Arthur F. Seelhorst Sr, had lived in Philadelphia during the Spanish Flu pandemic. He survived that, married in 1920, had two boys, then caught tuberculosis and died in 1924 at age 28. It was a long, slow death. There’s a reason it was called consumption. My dad was six months old, too young to remember his father.

Then my dad contracted TB as a teenager in the late 1930s. He had what they called the “rest cure”—and only added “cure” if it worked. He isolated and rested, hoping his body could keep the bacteria at bay. It took more than a year to recover. His lungs were never quite the same.

Yes, he isolated while he was contagious. Before penicillin became widely available after World War II—and even for some time afterward, dedicated TB hospitals were common, keeping patients away from others they might infect. Tuberculosis was far less transmissible than this new coronavirus—but today many people won’t even wear a mask, let alone agree to isolate as radically as TB patients once did. Luckily for him, he was able to isolate at home and didn’t have to go away.

Dad used to say, “In public health if you do everything right, nothing happens. But then when nothing happens, people think you went too far.” That’s what you want—nothing. No one dies, businesses don’t close, life isn’t disrupted. Imagine if nothing had happened in 2020.

Another of his favorites was “Public health is always underfunded and underappreciated.” That’s only gotten worse since he died twenty years ago.

After graduating from McKell High School in South Shore, Kentucky—delayed a few years because of his illness—he attended a vocational school, intending to stay in Kentucky and farm. He got married in 1951. He and my mom wanted to start a dairy farm, but such an investment was beyond their ability. So instead, Mom worked as a secretary in Portsmouth, Ohio, living with his mother on the Kentucky side of the river to save money while Dad went to school at Marshall University in Huntington, West Virginia. He lived on peanut butter sandwiches during the week and came home on weekends. (Mom said she went to see him at school once and found his closet full of empty peanut butter jars.) Yes, there were lots of Ohio River crossings–including when us kids were born. Everybody in that part of Kentucky went to the Portsmouth hospital.

Dad worked at first for the Vinton County Health Department, a rural county in Southeastern Ohio, then for Athens County next door. He inspected kitchens in public facilities and restaurants, tested well water, and investigated outbreaks of—well, I don’t know—whatever was breaking out. I remember getting a typhoid shot one year when the flooding was bad. Once be brought home a bat in a big jar. It had bitten a kid at a school he was inspecting, so he took it to the lab the next day to be tested for rabies. I wondered what would happen if the jar broke.

Then for about 30 years, he worked for the state, inspecting nursing homes for the Southeast District Ohio Department of Health. Yeah, nursing homes, where this new virus is gripping our elders and their caretakers with fear and far too often death. He’d be horrified at what’s happening in nursing homes today, residents cut off from their families and too often dying despite the best efforts of often underpaid staff at risk of illness from working without enough protective gear.

Every year, all the public health workers had to get a TB test. Every year, he told them it would come back positive. Every year, it did. The bacteria never really leaves–it goes dormant in calcified nodes in the lungs. TB literally dogged his life. (Now that I think about it, if not for tuberculosis, his father wouldn’t have died when he did, his mom wouldn’t have moved to Kentucky when she did, Dad wouldn’t have met Mom, and I wouldn’t be here.)

Two events in his state health department career stand out in my mind. First, a nighttime fire at a Marietta nursing home that killed a large number of residents. They didn’t burn to death—they died from smoke inhalation because the staff had propped open a couple of fire doors that were supposed to automatically close. And they didn’t notice the flashing silent alarm right away because they were watching TV. Dad came home reeking of smoke and spread out the facilities’ floor plans on the floor. I remember he had carpet samples he lit on fire in the back yard to see how much it smoked.

He said it was one of the best homes in the district. “Regulations don’t help if people violate them.”

The other standout moment was not part of his official duties, but informed by his education and experience. About 1980, Grandma Burke was in the hospital (yup, another Kentuckian treated in Portsmouth) with a respiratory illness that mystified her doctor. Dad went to see Grandma, talked to her a bit, then went to find her doctor. “Did you test her for TB?” he asked her doctor.

“No, we never see that any more,” he said.

“Did you ask her where she was this winter?”

“No.”

“Well, she was in Florida for a couple months. Every week, she used a laundromat frequented by Haitian immigrants. There’s been a sharp rise in tuberculosis in Haiti. And I had TB myself. I know the symptoms.”

He was right. She had TB. That night, Dad called me. “You went to see Grandma, right?”

“Of course!” I said defensively, thinking he was checking up on whether I had turned out to be a decent human being.

“Go get a TB test. Now!”

Contact tracing at its finest.

When I was in school, kids would sometimes ask what my dad did. “My dad’s a sanitarian.” They thought it was a euphemism for a garbage collector. In fact, picking up the trash is part of the overarching public health system. It’s not run by the Health Department but, like sewage treatment and municipal water systems, it’s critical to the health of our communities.

I used to wonder why garbage men didn’t make the most money of all. Why didn’t we pay people doing the exhausting and unglamorous and smelly jobs the most? If I could grow up lucky enough to be an artist or a musician, or a writer—well the joy of it would be worth a lot. The privilege of not having to pick up the trash would be worth a lot to me.

Little did I know then that A) most artists and writers and musicians don’t make much money either, and B) the world didn’t work that way.

Maybe it should. The essential workers of this pandemic are the folks with those exhausting and unglamorous jobs: the meat cutters, lettuce pickers, hospital aides, grocery cashiers, bus drivers, mail deliverers, and “sanitation engineers” of all types.

Dad collected several old quarantine signs and other health memorabilia over his career. When Mom could no longer climb the stairs to see them and object, he hung them on the bedroom doors at our house. Sanitation humor. (Yeah, one of them was for tuberculosis. I didn’t end up with that one.)

His old quarantine signs are reminders of the collective actions that communities were once willing to take until science and medicine could catch up and suppress disease. We became so accustomed to relying on science and medicine that we forgot the communal acts of public health that, not so long ago, were all we could rely on to protect each other and ourselves. We forgot what – and who – are essential.

I haven’t forgotten my dad. Even 20 years after his death I remember his smile, his voice, his laugh, and the lessons he taught us. They’re the simple ones. Wash your hands. Cover your cough. Take your medicine.

“If you don’t want to do it for yourself, do it for others.”

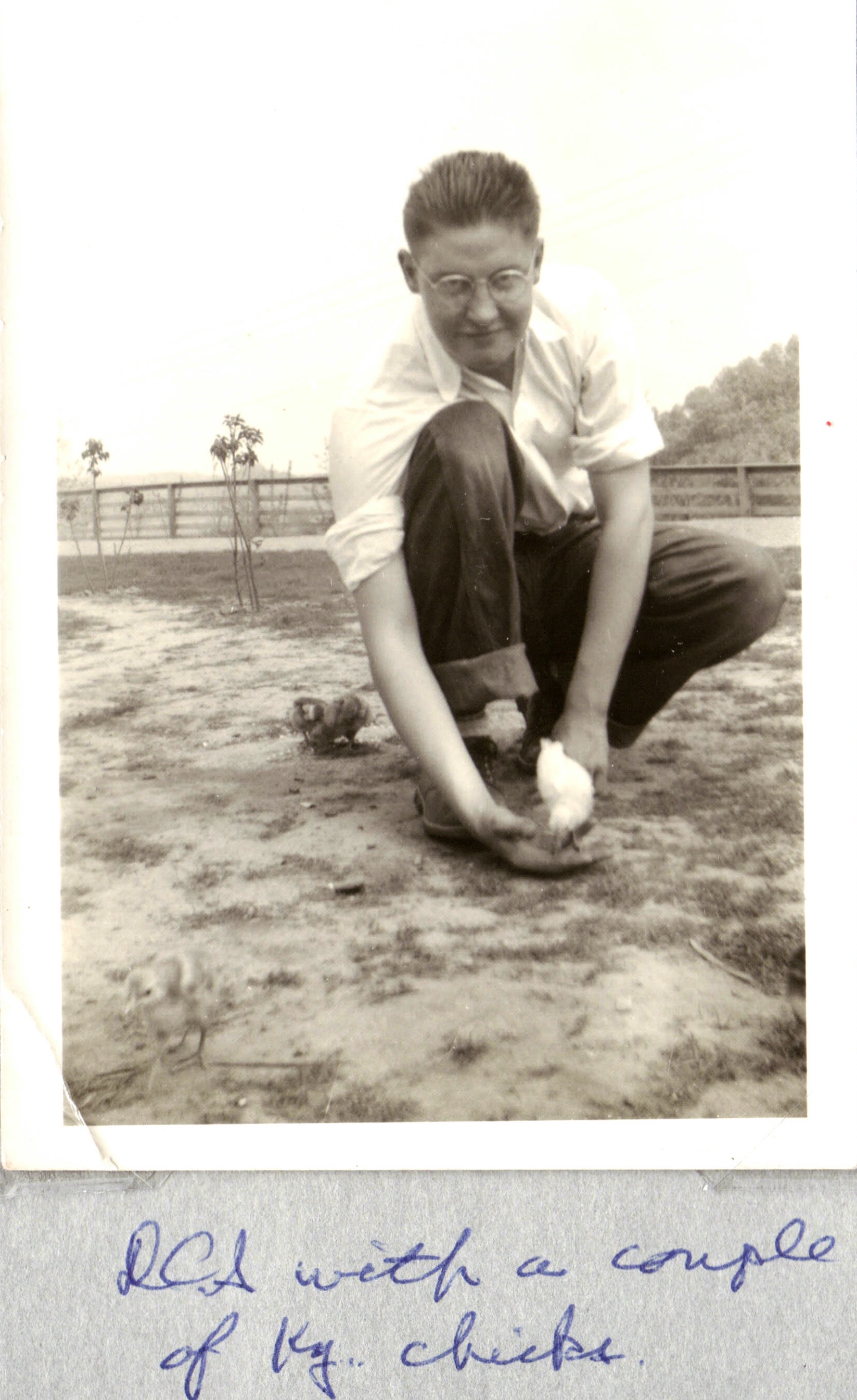

This is wonderful. There are stories here I had never heard! I didn’t remember that Grandma Burke had TB. Love the photos (Dad and his chicks… hahaha! He was SO skinny in that photo) and the quarantine signs. What Dad did was important. I always knew that. He made life better for countless people, and they never knew. If only there had been a smoke free office in the SE District Office of the Ohio Health Department. Thank you.

LikeLike

This is wonderful. Eager to share with CB. She will appreciate it. She went to U of Ky med school.

These stories also remind me of vague memories of growing up around Roanoke near sanatoriums and hospitals with fresh air porches. The stencils of the city market streets always intrigued me “No spitting”

LikeLike

I had TB. when I was 9 years old. I was in the NELSONVILLE OHIO SANITARIUM FOR ONE YEAR! I will be 74 in September and have tried to get my medical records from the hospital

What happened to the records? Were they destroyed once the hospital closed?

LikeLike

Just nine! That must have been so difficult. You are ten years older than I am, so you must have been there shortly before it was closed and turned into the health department offices. I have no idea where those records ended up. Maybe that’s a question for the Ohio Department of Health. I’m not sure if ODH ran the sanitarium or if it was another entity. I’m glad you found this essay, and than you for commenting.

LikeLike